Hello Readers,

Just a note to say I have migrated by blogging to substack where all my posts will be published. My url on substack is gchelwa.substack.com.

Thank you for reading.

Grieve

Hello Readers,

Just a note to say I have migrated by blogging to substack where all my posts will be published. My url on substack is gchelwa.substack.com.

Thank you for reading.

Grieve

By Grieve Chelwa

Close to three weeks ago, the Zambian government announced that they'd finally reached an agreement with official creditors to restructure some $6.3billion of external debt. The agreement allows for much longer maturities, concessional interest rates and a moratorium on principal repayments until 2026. Further, the agreement excludes domestic debt from being subjected to restructuring, which is a big relief. Requiring the restructuring of domestic debt would have been fatal for our nascent bond and financial markets.

The debt deal is certainly a welcome development that should provide much-needed fiscal space for government to (hopefully) undertake development-oriented projects. It is also worth pointing out that this deal only solves one part of Zambia's debt, which is debt owed to official entities (foreign governments, foreign official lenders, international financial institutions, etc...). Commercial debt, which is the other side of debt and owed to banks and bondholders, still remains unresolved (although reports suggest that a deal here too is eminent). The Ministry of Finance reported commercial debt as $5.91 billion at the end of 2022 (although this number is higher now due to the reclassification of some official debt as commercial debt).

In reading through the multitude of coverage on Zambia's deal, it struck me that the deal was effectively a deal with China. Several sources (see here, here and here) have reported that of the $6.3billion agreed to be restructured in the deal, about two-thirds (some $4.1billion) is money owed to the state-owned Export and Import Bank of China (EXIM China). The $4.1billion number is also what you'd get if you summed up all the money owed to EXIM China as contained in the Ministry of Finance's Public Debt Summary Statistics Report from last December (link here). Further, the features of the deal (maturity extensions, low interest rates, brief moratoria on principal repayments, limited haircuts, etc...) have the classic features of China's preferred approach to debt renegotiation/restructuring (see here, here and here for some of the academic evidence).

All this goes to show that the deal announced at the end of June was largely a deal with China. A columnist writing for Bloomberg on the deal rightly titled his article 'Zambia's Deal with China is a Landmark Moment'.

The above begs the question: What was the point of the Common Framework in this process?

The Common Framework, proposed by the G20, is supposed to be a mechanism to help poor countries resolve their debt problems by bringing together official creditors and borrowers. But for Zambia, which applied for debt treatment under the Common Framework over two years ago, the process was greatly slowed down as it became a sight for geopolitical shenanigans and posturing particularly by entities and countries that are no longer singularly important for the provision of credit to the global South and Zambia in particular. For example, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva used their visits to Zambia in January to cast China as the villain in the Common Framework process.

All the while that some folks were playing geopolitics with Zambia's debt, millions of Zambians, many of them crashingly poor, had to contend with the havoc wreaked by the uncertainties of unresolved debt. The value of the Zambian Kwacha has swung like a yo-yo in this long period of uncertainty causing a tailspin in the prices of essential commodities, many of them imported.

This is why at different stages in the process I, among some others, urged the Zambian government to ditch the currently inadequate multilateral approaches and rather negotiate directly with our creditors. All that we got with the Common Framework was a greatly delayed debt deal whose terms, as per the scholarly evidence above, are not materially different to what we'd have gotten had we gone directly to China in the first instance. Second, going the route of the Common Framework opened us up to yet another IMF programme whose conditions, as I have argued before on this blog, are anti-poor and anti-development in their design.

Zambia's experience shows that in this present moment of geopolitical reconfiguration, it is folly for poor countries to use the old, largely western-dominated multilateral system to resolve their economic crises. In the absence of genuinely fair and just multilateral arrangements, poor countries will need to take the initiative into their own hands to safeguard the interests of their citizens and those of future generations.

By Grieve Chelwa

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) yesterday published the conditions attached to the newly agreed programme with the Zambian government. The conditions are incredible, unbelievable, heartless and basically make for very sad reading. They are even more incredible than I predicted in my radio appearance on Hot FM last December. I spent this morning reading the IMF's document. Below, and typed up pretty quickly because of work pressures, I summarise some of the most concerning aspects of the "deal".

Last week, it was widely reported that president Hakainde Hichilema had signed into Law the Bank of Zambia Act of 2022. The new law replaces the Bank of Zambia Act of 1996. According to the accompanying memorandum from the Attorney-General, the new law has many objectives including providing for the establishment of a Monetary Policy Committee and a Financial Stability Committee -- both laudable initiatives.

However, one amendment that caught my attention, widely discussed and praised on social media, is the introduction of new clauses that guarantee security of tenure of the governor, who is the head of the Bank of Zambia. In the 1996 Act, the governor (and his/her deputies) did not have such security and could be summarily dismissed by the president. Article 10(7) of the 1996 Act read:

The Governor may resign from office by giving three months notice to the President and may be removed by the President.

Essentially this meant that the president could dismiss a governor at a moment's notice without the need to provide cause.

The new Act introduces security of tenure in Article 13 (in subsections 3 to 7). The basic gist of the amendment is that the president is now required to constitute a tribunal should he/she see the need to remove a governor (or any of the deputies). The tribunal is then required to carry out its investigations and submit a report with a recommendation to the president in about a month.

This amendment gives the governor the kind of security of tenure that is enjoyed by the likes of judges and the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) although interestingly (and perhaps curiously) the security of tenure of the governor is not guaranteed in the Constitution, as it is for judges and the DPP, but in subsidiary legislation (more on this below).

On the face of it, this amendment seems like a good thing as it buttresses the so-called independence of the central bank. According to the "independence thesis", central banks are sacred institutions that ought to be staffed by computer-like technocrats that are insulated from the vagaries and emotions of politics, leaving them to focus almost exclusively on technocratic concerns with price stability. (As a matter of fact, Article 5(2) of the new Act makes it explicit that price stability is the new god of our central bank and little else should sway their decision making).

But as careful scholars have demonstrated, central bank independence and its hyper-focus on price stability is a terrible policy constraining the ability of developing countries to fully transform their economies via, for example, large-scale industrialisation. Lots of scholars have documented how the now-developed and industrialized countries have historically used their central banks as tools of industrial policy that have deliberately directed financing towards strategic sectors of the economy. Writing in 2006, the economist Gerald Epstein had this to say:

…virtually throughout their history, central banks have financed governments, used allocation methods and subsidies to engage in ‘sectoral policy’ and have attempted to manage the foreign exchanges, often with capital and exchange controls of various kinds. The current ‘best practice recipe [of central bank independence with a narrow focus on price stability]’...goes against the history and tradition of central banking in the [developed] countries now most strongly promoting it…

And the distinguished Malawian economist Thandika Mkandawire writing about the South Korean experience had this to say:

[V]irtually all central banks have engaged in ‘industrial policy’ or ‘selective targeting’. In the credit allocating functions central banks have been “most effective in helping to foster development, especially in ‘late developers’ [such as South Korea], where they have been part of the governmental apparatus of industrial policy” (Epstein 2006). In South Korea, the Central bank was subservient, “nearly an administrative arm of the Economic Planning Board and the Ministry of Finance” (120)

Central banks, in the now-developed countries have historically viewed their societal roles as going beyond narrow and technocratic concerns with price stability. In so doing, these central banks have not been independent of the body politic but have been every bit a part of it, and in most cases subservient to it.

At this point in our country's development, the Bank of Zambia ought to be a vital engine of industrialization directly providing and directly facilitating the type of long-term capital required for meaningful (and not lip service) industrialization. We need the central bank to not shield itself from the people, but to be with the people and answerable to them as the "People's Bank".

Additionally, new academic work has shown that "independence" is often only in name. As a practical matter, so-called independent central banks tend to be beholden to the moneyed classes, a situation that has led to rising inequality in those parts of the world that have institutionalized such "independence".

In the Zambian case, it is also interesting to note that central bank governors have largely enjoyed sufficiently long tenures even in the absence of formalized security of the sort contained in this new amendment. For example, since 1992, the average tenure of office of a governor has been a healthy 5 years. If we exclude the lone year served by Christopher Mvunga, the average tenure rises to 6 years. In many ways, Zambian central bankers have enjoyed lengthy stays in office -- a situation suggestive of a healthy dynamic with their principals. For example, current governor Denny Kalyalya, during his first stint as governor, enjoyed a five year tenure in spite of his public disagreements with the policy positions of government. So why the need to secure tenure at this point in our country's development trajectory?

Lastly, my good friend Goodwell Mateyo, who recently appeared on Capital FM with Frank Mutubila, and a lawyer by training, has made the rather interesting argument that the new amendment might be in violation of the Constitution. Additionally, Mateyo has argued that matters around security of tenure ought to be reflected in the supreme law of the land, the Constitution, as opposed to subsidiary legislation as is the case with judges and so on. Also, the threshold to make a constitutional amendment is much more stringent than an amendment to an Act. Something as heavy as safeguarding the tenure of office of the governor ought to have been subjected to such a stringent criteria. You can listen to a recording of Mateyo's insightful interview with Frank Mutubila by clicking here.

Comments welcome: grievechelwa@gmail.com

Yesterday, Minister of Mines Richard Musukwa announced that the Zambian government had decided to fully take-over Mopani Copper Mines (MCM) by purchasing Glencore's and First Quantum Mineral's combined 90% stake in the mine. Prior to this, government's shareholding in the mine was 10%. Specific details on the transaction are still very vague. However, the clearest statement on the deal so far is from Minister Musukwa's speech on the transaction (pdf available here). In this hurriedly written post, I want to recount the main points of the transaction as detailed by the minister and provide some reflections on the same. I hope to write more substantively about this in the coming days when more details are hopefully made available.

Before engaging with the minister's points, I want to say that I wholeheartedly agree in principle that we as a country need to fully own and run our copper mines. One of the biggest policy mistakes of the last 25 years or so was the decision to privatize the copper industry. In his 2015 Goma Lecture presented in Lusaka, the late economist Thandika Mkandawire estimated that Zambia would have accrued national savings of about $20bn had we never sold the mines. And these savings would have been deployed towards productive investments and large-scale social spending negating the need to borrow from external sources. Selling the mines was a big mistake.

The three main features of the transaction announced yesterday are the following (this is taken verbatim from the minister's statement):

1. The $4.8bn loan owed by MCM has been agreed to be reduced to $1.5bn. MCM as an asset was owing loans amounting to $4.8bn from Glencore (Bermuda), Glencore International and Carlisa.

2. The sale price is $1

3. The [$1.5bn] loan [mentioned in point 1] is to be repaid through an off-take agreement granted to Glencore International using 10% of the production. That means the loan will be repaid between 10 and 17 years depending on the price of copper. You may wish to know that prior to this transaction Glencore already had an off-take agreement with MCM and this is expected to continue.

Point 2 is merely academic and so I won't spend time on it. Points 1 and 3 are where the action and the controversy is in my opinion. Let's start with point 1 and then go to point 3.

On Point 1

The point basically says that MCM, itself a Glencore entity, had over the years received financing of upto $4.8bn from three Glencore entities (Carlisa is majority-owned by Glencore with minimal shareholding from First Quantum Minerals. From the look of things, Carlisa, based in the British Virgin Islands, was set-up to manage Glencore's and First Quantum's investments in MCM). As part of yesterday's transaction, Glencore (or Carlisa which is really the samething) want the Zambian government to assume this loan which the previous owners have "graciously" written down to $1.5bn.

There are several issues that are problematic about this. First, is there anyway to prove that this was an actual loan and not a notional one? This is not an easily dismissible question given the overwhelming evidence showing that multinationals, especially those in the extractive sector, often use intra-company loans as an effective mechanism for tax avoidance.

Second, the $4.8bn was a loan from the parents to the subsidiary. In other words, the parents invested in their child and these investments did not work out. Why should the Zambian people pick up the tab of the parents' misjudged investments? The discussion would be different if the loan had been issued by, say, an independent bank with limited control over MCM. Glencore were fully in-charge of MCM when these loans were being granted. It appears that the investments amounted to nought. Glencore should completely write-off these loans and consider them bad loans.

Third, the implication of all this is that the actual/effective selling price of the 90% shares in MCM is $1.5bn (the so-called $1 selling price is a distraction). The Financial Times reports that Glencore had in August 2020 valued MCM at $700mn. 90% of $700mn is $630mn and not $1.5bn. We are clearly overpaying (and possibly over over over paying if it turns out that the $4.8bn was a notional loan).

On Point 3

This point basically says that Glencore wants to guarantee the payment of its loan by guaranteeing for itself 10% of MCM's copper output from now until the $1.5bn loan is repaid. The minister reckons that this arrangement might be in place for about 12 to 17 years depending on the performance of the copper price. All this assumes a healthy outlook for the copper industry over the medium to long-term. But what happens when the copper price plummets below healthy? What will Glencore do? Sell the loan onto Vulture Funds? Repossess Zambian assets?

These are not unreasonable questions given the well-known history of boom and busts in the commodities markets. (As an aside, the current debt crisis engulfing the African continent is partly the result of rosy commodity price forecasts that were floating around circa 2009/2010).

Second, between points 1 and 3, point 3 is the vaguest in terms of actual details. What, for example, is the implied interest rate for this loan? We need to know this so that we can compare whether it would have been cheaper to borrow the $1.5bn via another vehicle (bank, capital market, etc...) and immediately pay-off the Glencore loan. I suspect that the implied interest rate on this loan is exorbitantly high. It is even higher if you include the opportunity costs associated with being forced to sell 10% of your copper output for the next 2 decades to a private entity. For instance, MCM would have to turn down some other buyer wanting 100% of its copper at a price offer above the market price. This would be a loss to MCM and the country.

We really need more details on point 3 given all this.

Can Zambians Run Mines?

Before concluding I want to deal with the age-old question of whether Zambian's can run the mines.

As I stated at the outset, I am all for the country owning the mining industry. An objection often raised when I make this point is that Zambians do not have the know-how to run mines. The evidence those arguing this way produce is the performance of copper production under ZCCM in the 30 year period (1970 to 2000) that Zambia had a controlling stake in the entire mining industry (ZCCM which stands for Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines was the conglomerate that ran the mines). For those arguing this way, the relative success of the industry under private hands (since about 2000) is further evidence in their favour.

As I argued in a piece for Africa Is A Country in 2015, the story of Zambia's copper production is really a story of the copper price. In times when copper prices have been high, so have been production and profitability. In times when prices have been low, so has production and profitability. Specifically in 2015 I wrote:

In the decade running up to nationalization (1960 to 1968), real (inflation-adjusted) copper prices increased by 69%. In the three decades after nationalization but before privatization, copper prices performed as follows: a 45% decline in the 70s, a 7% increase in the 80s and a 39% decline in the 90s. Over the entire period 1970 to 1999, the real (inflation-adjusted) price of copper declined by an incredible 70%!...Between 2000 and 2010 [after the mines had been sold to private hands], real (inflation-adjusted) copper prices increased by a whopping 230%! Anybody, be it a state-run entity or private entity, would have responded to this incredible rise in copper prices by producing more [and registering healthy profits].

Our prayer then is that copper prices should be in our favour as we enter this new era of "re-nationalization". Our second prayer is that the Patriotic Front government manages this God-given resource prudently and for the benefit of all Zambians. This is a big prayer given recent corruption scandals that have hit the party.

Zambian social media platforms, especially WhatsApp groups, were very active yesterday sharing and discussing the publication of the World Bank's latest International Debt Statistics Handbook. I've lost count of the number of friends on WhatsApp who sent me the hyperlink to the download page of the book. Ordinarily, the publication of the Debt Statistics Handbook goes without notice in much of the world and especially in Zambia. So why all this interest this time around?

Well, in the last couple of weeks, "Zambia and its debt" has been a topical issue with prominent coverage in the Financial Times and Bloomberg among other international outlets. The latest round of interest comes on the heels of an official request from the Zambian government for a payment holiday on upcoming debt service obligations. So this week's publication of the World Bank's International Debt Statistics Handbook (hereafter IDSH) fell into this milieu of strong emotions around Zambia and its debt.

So why all the fuss? Well, all the commentary on WhatsApp, Twitter and Facebook on the the IDSH zeroed in one single statistic reported at the top of page 150: Zambia's external debt at the end of 2019 was $27 billion dollars! This is certainly a huge number and would suggest that the country's external debt was almost equal to the size of the country's GDP. And for many of yesterday's commentators, this number was evidence that the Zambian government was understating the true nature of its external debt. For example, Finance Minister Bwalya Ng'andu recently told parliament that external public debt was $11.97 billion dollars, a number that is about $15 billion lower than the World Bank's number.

So what is going on here? The confusion stems from the conflation of Total External Public Debt with Total External Debt. The two aren't the same thing even though they seem like they are.

Total External Public Debt (the first one) refers to all foreign denominated debts that are owed by the Zambian government. This includes external debt directly owed by the government and debt guaranteed by the government but contracted by government or quasi-government entities. For example, Total External Public Debt would include the (in)famous Eurobonds and/or any guarantees issued by the government in favour of, for example, the Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation (ZESCO).

Total External Debt, on the other hand, is the sum total of all the external debt owed by entities domiciled in Zambia. This includes debt owed by the Zambian government (as defined above) and that is owed by Zambia's private sector. Total External Debt would include external debt owed by the government plus external debt owed to foreign creditors by, for example, the privately-run mining industry.

By definition, and given the above, Total External Public Debt can never exceed Total External Debt. The two can be equal which would imply that all external debt is government debt. In practice, Total External Public Debt tends to be lower than Total External Debt primarily because the private sector also borrows from foreign creditors.

So what does all this mean for the publication of the IDSH and the commentary that followed? Well, the first thing is that the World Bank and the Zambian government are saying the same thing. The fourth line item on page 150 of the IDSH says that Total External Public Debt at the end of 2019 was $11.1 billion [1]. Minister Ng'andu told Parliament on 25th September 2020 that "[total] external public debt stock increased to US$11.97 billion as at end-June 2020 from US$11.48 billion at the close of 2019...". As one can see, these numbers are pretty much around the same ballpark.

The June 2020 number, as reported by the Minister, is slightly greater than the 2019 numbers (from the government itself and the World Bank) because of the likely accrual of additional external public debt in the first 6 months of 2020. The 2019 numbers by the World Bank and from the government are slightly different from each other because of likely accounting/reconciliation issues. Interestingly, government's number for end 2019 is greater by about $300million. This might be the result of one public guarantee or the other that was not captured by World Bank statisticians.

So in many ways the World Bank's IDSH is telling us nothing new beyond what the government has already told us regarding the country's external public debt.

As to whether the $11 billion number (from both the World Bank and the government) is to be believed is a different question altogether. I have good reason to believe that the "true" external public debt is around this figure. Margaret Mwanakatwe, Ng'andu's immediate predecessor at Finance, instituted a debt reconciliation drive about two years ago and committed the Ministry of Finance to issuing quarterly debt briefings (although the frequency of the briefings has reduced lately). This was in response to heavy domestic and foreign criticism that the Zambian government did not know the true extent of its debt obligations. It appears the Ministry of Finance has gotten on top of this issue and, for example, recent IMF statements on the country are no longer broaching the subject of debt reconciliation as they did a couple of years ago. Economist Trevor Simumba, however, believes the true extent of external public debt might be higher owing to the opacity around debt contraction from China. He might very well be right.

Before concluding, I want to briefly talk about one aspect that struck me from the IDSH that few talked about yesterday and that I had been unaware of. According to page 150 of the IDSH, Zambia's private sector owes a whopping $14.7 billion to foreign creditors! In other words, private multinational corporations, private companies and private individuals all domiciled in Zambia collectively owe about 54% of Zambia's Total External Debt (recall the definition of this from above). This implies that Zambia's private sector is just as indebted to foreign creditors as the Zambian government is. In actual fact, the private sector owes much more.

As a country, we have not debated and thought about private sector debt as much as we should. It's worth engaging with this issue because, for one thing, economic crises can result from the unsustainable buildup of external debt by the private sector (see the Asian Financial Crisis) just as much as they can from unsustainable buildup of public debt. Second, pressure on the domestic currency (the Kwacha) can also arise from the demand for foreign currency by the private sector to meet its external debt obligations just as it can from demand by the government. So in a nutshell, any talks about devising a strategy for Zambia's external debt should include discussions about external debt held by the private sector.

Notes

[1] The IDSH refers to it as "Public and Publicly Guaranteed Debt"

"(2) The functions of the Bank of Zambia are to— (a) issue the currency of the Republic; (b) determine monetary policy; and (c) regulate banking and financial services, banks, financial and non-banking institutions, as prescribed."

"(2) The function of the Bank of Zambia is to formulate and implement monetary policy."

"So it seems that the Draft Amendment Bill seeks to strip away from the Central Bank the functions of issuing currency and the regulation of the financial sector. These two functions are pretty core to what central banks do across the world. And I can't see how another entity would logically takeover these functions, particularly the one to do with issuing currency. And the Draft Amendment Bill is silent on where functions (a) and (c) will now sit.

This is a strange amendment and one hopes that Members of Parliament will probe for details and justifications once the Bill is tabled in the National Assembly."

"The proposed provisions relating to the Central Bank were motivated by the Bank which is of the view that the Constitution should only contain broad constitutional principles which are operationalised through detailed legislation passed by Parliament. In this regard, the Bank submitted proposals for amendment of the Constitution regarding the Central Bank's functions to be restricted to the primary function, while additional functions, objectives and powers will continue to be subject of an Act of Parliament as envisaged under Article 215 of the Constitution of Zambia, Act No. 2 of 2016.

The Bank has thus submitted to the Government that the primary function of the Bank should be to formulate and implement Monetary Policy. This submission is consistent with best practice on central banking and also complies with the SADC Model Law for Central Banks which stipulates that all Central Banks in the region should move towards adopting a single primary objective."

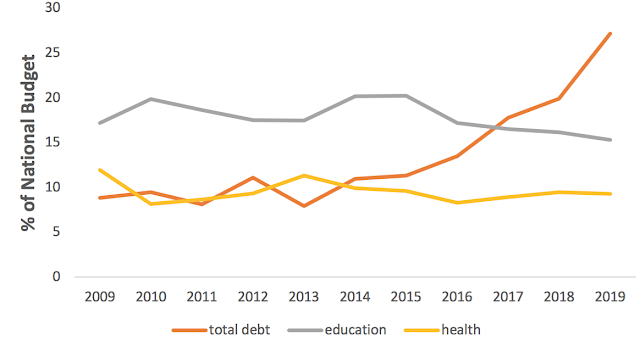

Our non-discretionary expenditure, which comprises personnel emoluments and debt stands at 50.1% and 40% respectively, giving a total of 90.1% of our annual budget. This leaves the discretionary expenditure amount to stand at 9.9% of our annual budget. This Mr. Speaker is an alarming ratio.

|

| Figure 1: Total Debt Service Share in the National Budget Source: Various National Budgets |

|

| Figure 2: Total, Domestic and External Debt Shares in National Budget Source: Various National Budgets |

|

| Figure 3: Total Debt Share, Education Share and Health Share in National Budget Source: Various National Budgets |

71. Article 213 of the Constitution is amended by the deletion of clause (2) and the substitution therefor [sic] of the following: (2) The function of the Bank of Zambia is to formulate and implement monetary policy.

213. (1) There is established the Bank of Zambia which shall be the central bank of the Republic. (2) The functions of the Bank of Zambia are to— (a) issue the currency of the Republic; (b) determine monetary policy; and (c) regulate banking and financial services, banks, financial and non-banking institutions, as prescribed.

|

| Figure 1: Total Foreign Assistance as a percentage of the total budget Source: National Budget Speeches, 2007 to 2018 |

|

| Figure 2: Different components of total assistance as a % of the total budget Source: National Budget Speeches, 2007 to 2018 |

|

| Figure 3: Components of the portfolio of donor "assistance" Source: National Budget Speeches, 2007 to 2018 |